The Army within the Russian empire

General John Larsson quotes Catherine Booth from 1880 in his foreword to my book: Lutheran Salvationists?: “The Army’s achievements are built on the great fundamental principle of adaption.” This can be seen in the Army’s history in different places in the world and has a unique expression within the Lutheran Nordic countries. The Army in Finland illustrates this very well.

When the Army started in Finland, it was part of the Russian Empire as a Grand Duchy with the Tsar as the Grand Duke. This situation had been the case since 1809 until the revolution in 1917, when the Finnish Senate approved independence 6. December 1917. This was confirmed by the Soviet government 31. December and finally by the Soviet Central Committee 4 January 1918. In 1809 it was agreed that the Lutheran faith could continue as the faith of the Finnish people and the Lutheran Church carry on as usual, only with the exception that the Lutheran Swedish King no longer was the head of the church, but instead the Orthodox Russian Tsar became the head of the Lutheran Church.

The same year as the Army started in Finland (8 November 1889) a dissenter law came into being, which gave the possibility of dissenting from the Lutheran Church and make free churches. It did not give general religious freedom as for instance for the Jewish community or any movement that had international connections. The Evangelical Movement and Pietism had a great influence in Finland, especially in the Swedish speaking aristocracy and middle and upper classes. Evangelical minded people from these classes gathered for evangelical revival meetings and engaged in social work among poor people. Some of them had heard about the Army and read its literature, some even had relatives in other parts of Europe who knew about the Army, and a few had joined the Army. This group from the Evangelical Movement took contact to William Booth in London in order to investigate the possibilities for an Army presence in Finland.

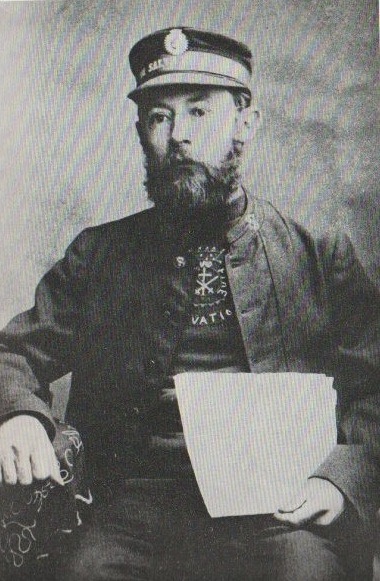

I will mention the leading persons within the Army’s beginning, who came from this background: Louise af Forselles, Constantin Boije and Hedvig von Hartman. Constantin Boije, apart from being heir to an estate which his mother run at this moment, also engaged himself in preaching. He passed the exam for lay preachers within the church, and this gave him the right to preach in Lutheran State churches and participate in the teaching within the Church. After the initial contact and negotiations with William Booth, Constantin Boije and Hedvig von Hartman travelled to London to be trained as Salvation Army officers. I will draw a few lines to give the background for the choices made at the beginning of the Army’s presence in the country. The foundation was as mentioned the Evangelical Movement within the Lutheran Church. The founding people of the Army were raised in families at different estates in Finland, and some of them were owners of estates. They were cultured, well informed people who mastered several languages, and most importantly they were burning evangelicals.

Being part of the Russian Empire, even though it was as a separate Grand Duchy did not give a lot of freedom for being registered or accepted legally as independent faith communities. The Russian Empire never practiced religious freedom and tried to avoid religious movements who differed from the Orthodox church, especially movements which were international. The Finnish Senate rejected the Army’s proposals for some sort of registration several times, but this did not hinder the work as it was possible for the pioneers as members of the Lutheran Church to propagate evangelical faith and to relieve poverty by doing social work. The Army was different and more visible than the other evangelical movements in Finland and added to this, there were warnings against its theology and work from within the church, but the noble descent and position of the founding people gave the Army some credibility and made its work possible. Constantin Boije’s authorization as a lay preacher within the church was another door opener. The battle for getting some sort of legal acceptance or registration was long and rather unsuccessful. The question of internationalism was of great importance. Actually Constantin Boije wrote William Booth on this question and was given permission to form an independent Finnish Salvation Army. This happened in a telegram with a follow up letter of 21 November 1889. By this permission the Army would be a special, separate national organization, which could carry the Army’s name and work under its flag. Boije never pursued this, but even so a schism happened between the founding people the following year, whereby Hedvig von Hartman became the leader, and Boije returned to his estate. He kept a fine relationship with William Booth who always received hospitality at Boije’s household when visiting Finland. Boije’s connection and friendship with the Army continued through the years and became crucial when the Army in Finland saw a possibility of opening of the Army’s work in Russia in 1913. Boije’s daughter, Helmy Boije, became a Salvation Army officer and was serving in Russia during the Russian Revolution. In spite of the freedom to choose an independent role the Army in Finland stayed as part of the international Army, but legal acceptance still made slow progress. Finally 14 July 1898, it registered as a housing association, nearly nine years after it began its work. Later it registered as a foundation, 31 July 1941.

A question which was of utmost importance was expressed when the Army in Finland tried to expand its work into Russia in 1913: “Do we want to reach the whole population or become a protestant sect?” The Army in Finland had answered this question for its own part. It wanted to reach the whole population and the whole country and it did. Its members stayed within the Lutheran Church, which was accepted by the Tsar as the faith of Finland, and used the right as members of the Lutheran Church to propagate their faith and gather in corps communities. They did not dissent from the faith and church of the country. An interesting example is a smaller alteration to the doctrines in the first War Cry from 25 April 1890, which were printed in the paper. It is clear from this that doctrine 8 had been removed. It reads: We believe that we are justified through faith in our Lord Jesus Christ and that he that believeth had the witness in himself. It cannot have been the part concerning justification that was problematic, but it must have been about having the witness in himself. This might not have been acceptable for the Lutheran Church, at least it would be met with some hostility. Otherwise the Army in Finland has through the years been loyal to the international Army in translations of doctrines and doctrine books, very different to Norway who used another mode of accommodating itself to the Norwegian church and society.

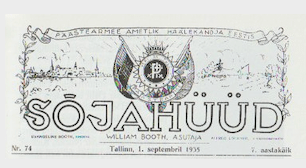

Other challenges for the young Army in Finland were the years of russification, where the Russian authorities tried to make Finland more Russian. The Russian Orthodox Church was given more room and privileges in Finland as a challenge to the Lutheran Church. In a situation like this being Lutheran became important, because it also meant being Finnish. Because of this situation there would be no inclination to form an independent dissenter community for the Army. It was important to guard the religion of Finland (this is my interpretation) in light of the pressure from the process of russification. The periods where the pressure were most severe were from 1899 to 1905 and 1908-1917. The first period was the Army’s adolescence years. Even before this period expatriate officers were sent out of the country – they were Swedish and Norwegian – because the authorities did not want foreigners. Just before the difficult period the Danish couple Jens and Agnes Poulsen became leaders in Finland in 1898 following the pioneer Hedvig von Hartman. Short after their arrival General Nikolai Bobrikov became Governor over Finland. Censorship was intensified, papers had to close, the freedom to gather and to make societies were tightened. The right for the Empire to govern without involving the Finnish Senate was taken and manifested, Russian became the language of the administration of the country, the Finnish military Army became part of the imperial Russian Army and so forth with the outcome that a number of difficulties followed these decisions. The Salvation Army tried to do what it could to down scale the international nature of the Army, for instance could Jens Povlsen as the TC not appear as the publisher of the War Cry. Jens and Agnes Povlsen managed to steer though this situation even to the degree that the Army grew and expanded its work. They stayed for five years and were followed by Swedish and British leaders during this period.

This gives just a small glimpse of the formation of the Army in Finland under the pressure from the Russian authorities. It also explains the choice to stay Lutheran and to keep personal bonds to the church. It had to do with religion and Lutheranism, but equally as much with nationality, being considered true Finnish both for oneself and others.

Expansion into Russia

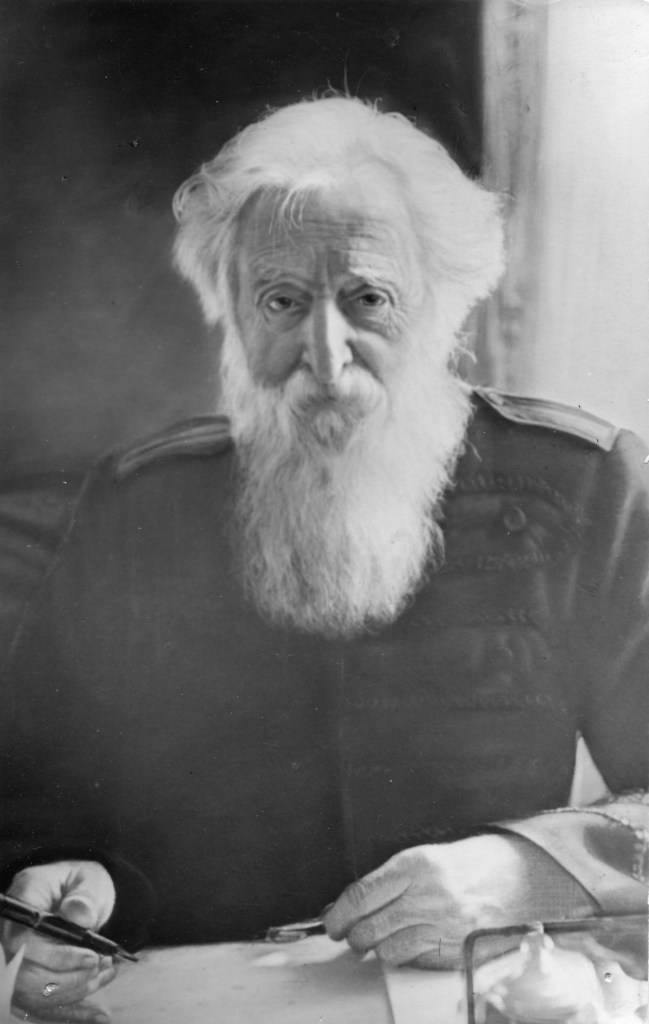

There was a wish from William Booth to start the Army’s work in Russia itself. He visited Sankt Petersburg in 1909 in connection with leading the Finnish congress. He was well received, again it was the upper class and nobility that were the hosts for this. The decision was to send somebody there to further investigate the possibilities. The choice fell on Jens and Agnes Poulsen who at that time were Chief Secretary in Denmark, but had a deep insight to the situation due to their time as leaders in Finland 7 years earlier. Nobody knew where they were going in 1910 when they left Copenhagen, only when they had arrived it was revealed. They stayed in Sankt Petersburg for one and a half year, but had to realize that the prospect of starting the Army seemed too difficult because of different political developments.

An opening came, when in 1913 there was an exhibition in Sankt Petersburg where the Army had a pavilion in the Finnish sector, where it showed its social work. Karl Larsson was the Territorial Commander. He looked for opportunities and found one. A man of Jewish Polish descent came in contact with the Army. He worked within the publishing trade. The idea was to publish a paper in Russian. He became the editor and Constantine Boije agreed to appear as the owner of the paper. His name and position opened this opportunity. Because of the paper it was possible to employ salesmen to sell papers in the streets of Sankt Petersburg. The salesmen became two Finnish women officers, Elsa Olsoni and Henny Granström. They moved to Sankt Petersburg and lived there. The flat which they shared with the editor and his family became the place for evangelical meetings. The soldiers who were enrolled became soldiers of Helsinki 1. Corps. The officers were allowed to sell the papers in the trams running the streets of the city. The circulation of the paper rose from 6.000 to 8.000 a week (2.000 of these were sold at different corps in Finland). A soldier who became a great help during this time was an estonian woman of the aristocracy who became a soldier during the congress in Finland in 1913, Marie von Wahl, and later an officer. She spoke Russian, German, English and as an officers learned Swedish.

The work grew in spite of difficulties, because of great creativity from the Army’s side. The central question was asked: “Shall we reach the whole population or become a protestant sect?” The answer was that the goal was to reach the whole population. How could this be done in an Orthodox country, how could the Army become a Russian Salvation Army as it had become a Finnish Salvation Army? How could it appear to the Orthodox Church that it did not want to harm or split the church, but that it was in harmony with the essentials of the Christian faith, the essentials of the church. My interpretation is that such an evaluation came on the agenda, because of the way the Army in Finland had accommodated itself with the Lutheran church.

Karl Larsson gave 5 directions in this process of enculturation:

- The Icon. People looked for the icon to see if the place was a proper Christian place, both in social outreach as well as in the meeting room, so Icons would be there. The rule within the Army was that the Icon had to be an Icon of Christ. It was placed on the side wall between the platform and the seating so nobody had to turn their back to the Icon at any stage, as this would not be proper.

- The sign of the cross. That could be used by the Orthodox members. It became a custom to ask one of the orthodox members to make the sign of the cross before the meetings started. At some stage it also became usual to sing the Lord’s prayer united after Orthodox tradition.

- There was given permission to wear a cross in a chain close to the body, which was a sign of Orthodox confession.

- It was also given free for personal choice to go for confession and Eucharist once a year in connection with Easter. A soldier said that she fell she gave her testimony to the priest. After some time the soldiers who always used their uniform felt that they were not welcomed by the priest.

- Questions concerning infant baptism, marriage, and funerals which were important rituals in the church and which people were connected to were not dealt with officially, but people slowly started to view them in a different light and did not feel they were absolutely essential for Christian life.

Karl Larsson had a comment that he was not sure these rules had the permission of the General, but the General had not sent out a ban either. I am sure the influence from accommodating successfully into the Nordic Lutheran setting was the reason for making such guidelines for the Orthodox Salvationists in Russia.

Estonia

The history of Estonia is different. The Lutheran Church used to be the dominant church for the majority of the population like in Scandinavia, but we do not have any indication of the Salvationists’ attachment to the church during the 12 years the Army had a presence in the country before 1940. It obtained a registration 27 November 1927, but a new law concerning churches and religious communities from 13 December 1934 did not include the Army. The Minister of Internal Affairs, when asked by the Army, said that the new law would not limit the activities of the Army. After 1940 when the Salvation Army was banned most Salvationists connected to the Methodist Church. During Soviet times the persecution of the Lutheran Church had as a result that the membership of the church fell from 875.000 members to 175.000.

Because the large percentage of Russians who lived in Estonia had no affiliation to the Lutheran Church and because of Soviet occupation the pattern seen in Finland and the rest of Scandinavia concerning membership of the Lutheran Church has not been relevant for Estonia. National identity is not bound to being Lutheran, at least not any longer.

However, in August 2017 the Lutheran Church in Estonia could celebrate 500 years for the Reformation in cooperation with the state. The Town Council of Tallinn arranged an exhibition together with the Estonian Lutheran Church at the Town Hall. Tallinn’s historic museum opened an exhibition concerning the century of the reformation. A number of people, teachers, artists, intellectuals, museums people have participated in the arrangements. It at least shows that the government and the establishment are aware of the history of a Lutheran majority church.

Today both the Army in Russia and Estonia are registered as evangelical churches.

Search for identity

As history developed so differently in the three countries, I have mentioned, the implications of the question: Do we want to reach the whole population or become a protestant sect? are different.The similarities disappeared as history changed and communism became dominant. The Army was forbidden 27 February 1923 in Russia for anti-Soviet activities, and the contact to the international Army ceased. All Christian communities, also the Orthodox Church experienced persecution and closure of churches. There were periods of severe persecution, and times when things were more calm. The Army was forbidden in Estonia in July 1940, but Salvationists who had fled Estonia during the war kept contact to their fellow salvationists in Estonia. The Army in Finland kept contact by Finnish Salvationists visiting Estonia for ‘birthday parties’, and here in private homes they could sing the old songs and share the Scriptures with each other, and enjoy fellowship. A number of Estonian Salvationists joined the Methodist church in the following years, and the decrease of the influence of the Lutheran church meant that Estonian Salvationists would not be influenced by a Lutheran state or majority church. The Army had its roots in the Methodist church, so the Salvationists there became connected to the Army’s roots.

Even though Finland were involved in the Winter War and the War of Continuation, where it lost an important part of the country, the religious situation did not change. For the Army the loss was a very vibrant and big Army in Karelia, especially in Viborg, but the Finnish Salvationists living there fled or rather were expelled to Finland like the rest of the population and spread all over the country. They were not lost as Salvationists, but the vast number of young men who died had an impact also on the Army as their number included Salvationists.

In times of upheaval or thread from the outside, it has been important to hold on to all that unites a nation and the Lutheran Church has been such a uniting factor in Finland as most Finns belonged to the church. Because of this Finnish Salvationists seemingly did not want to dissent from such a situation.

The Army wanted to reach the whole population and it did. It was strong and very well received by all, including ministers and bishops in the Lutheran church. The bonds to the church were strong. Tor Wahlström tells how it was custom for a TC when visiting a Cathedral town to pay a visit to the Bishop as a courtesy. The tradition with a Lutheran minister performing the funeral of officers and soldiers has long roots and is still the case today.

In the late 1960s and further on in the 1970s a search for identity took place in different countries and within different churches. In the Catholic Church the Second Vatican Council finished in 1965 and one of the eleven documents from the last gathering was Gaudium and Spes (Joy and Hope). It confirmed that the church had the duty to scrutinize the signs of the times and interpret it in light of the gospel. A similar agenda took place within the Norwegian Church at the same time and questions concerning identity as a faith community began within the Army in Norway and came to the forefront in a Salvation Army Commission, that worked with the issue in 1975-78. In Finland Tor Wahlström worked with his dissertation concerning the Army in Finland as a faith community. It was published in 1975.

1 January 1973 he made a questionnaire to find out the percentage of membership of Salvationists in other churches: The whole population:

Lutherans 96.8% (2.686) 92.1%

Orthodox 0.6% (17) 1.3%

Free Church 1.9% (53) 0.3%

Civil Register 0.7% (19) 5.8%

This shows that there was a higher percentage of Lutherans among Salvationists than in the population as such, the same with the percentage of Free Church members, while the percentage of Orthodox Salvationists were lower and so were those from the Civil Register. Wahlström calls Finland the most Lutheran country in the world.

Also in 1973 the Army in Norway made a research of Salvationists’ double membership. There were 11.680 soldiers and 11.516 were members of the Norwegian Lutheran Church. 54 were members of the Pentecostal church, 47 of the Methodist church, 16 of the Baptist church, 19 of the Free Mission and 1 was a Catholic. 28 soldiers had the Army as their only membership. It was well over 99% that were Lutherans, so even higher than Finnish Salvationists. It was higher than the country as such. In Finland as well as in Norway some Salvationists served on church boards of the local Lutheran churches or had their work within the church.

Wahlström made another questionnaire in June/July 1973 where active officers should choose from seven given definitions of the Army:

Christian/Social organization 49.1% (88)

Revival movement 6.1% (11)

Evangelization movement 5.5% (10)

Evangelization and Social help organization 37.0% (66)

Free Church 1.7% (3)

Sect zero

An order within the general church 0.6% (1)

It was clear that nobody wanted the Army to be seen as a sect, but also that so few wanted the Army to be seen as a free church, only one could see him/herself as member of a religious order. The two that were accepted as describing the identity were when Christian or evangelization were linked to social organization. It says a lot about the identity at this time in 1973. Wahlström wanted to identify who or what the Army was in sociological as well as theological terms. His conclusion of his search for a definition was:

“The Salvation Army in Finland is an integrated part of the international movement, and at least in this country appears as an order within the universal church. This order regards it as its task to operate as a revival movement, especially among people who are estranged from Christianity and the church, to encourage holiness among the Christians, and to perform social work anywhere the need of society and human distress appeal to the Christian conscience for help.”

Several times in his dissertation he used the term Lutheran Salvationists, but not in his conclusion as he pointed to the fact that The Salvation Army could not be linked to any specific church as a religious order. The search for identity was not only Norwegian or Finnish, but international and could be seen in an article by General Wiseman from 1976 called Are we a church? Wahlström’s research seemed also to be influential internationally even though his dissertation was written in Swedish as it could be seen in this article:

“There are Salvationists in some parts of Scandinavia who up till now appear to have little difficulty reconciling membership in a State Church with membership in the Army. It must be said that this duality has in no way diminished their devotion, but it does raise an important question: should the Army in such circumstances be looked upon as a religious order?”

In Norway the commission discussed this and argued that Norwegian Salvationists were not as influenced by Lutheranism as Finnish Salvationists were, but that the definition religious order could be defended in Norway as well, especially seen in historic retrospect.

Wiseman stated that if this concept and an association to the State Church had allowed people to keep loyal to the Army they should be considered part of the composite picture of the Army, as long as the movement possessed freedom and autonomy to maintain its identity and function. He stressed the grace of flexibility. He could have quoted Catherine Booth’s statement: “The Army’s Achievements are built on the great fundamental principle of adaptation.”

It is clear that there was a search for identity at this time. So many changes took place in society as secularization, youth uproar with a wish for democratic rights at the schools and universities, women’s liberation, the expansion of the welfare state. The television came into most homes and different programs, that placed another agenda than what was known in more pietistic circles such as the Army, challenged traditional beliefs and values. The TV also showed films and theatre that were foreign to many Salvationists. Charles Taylor describes the situation such:

“From a society where belief in God is unchallenged and indeed, unproblematic, to one in which it is understood to be one opinion among others, and frequently not the easiest to embrace”…or “a society in which it was virtually impossible not to believe in God, to one in which faith, even for the staunchest believer, is one human possibility among others.” (Taylor, A Secular Age,3)

Salvationists were not immune from general secularization either. They, too, experienced that belief in God was not the ‘easiest to embrace’. Especially the young people were trapped in this and a number left the Army. I think the number of these were higher in Finland and Denmark than in Norway. I do not know how the Army in Finland handled this situation, but I know what Norway did in order to meet this search for identity.

In Norway this search for identity was evident within the Norwegian church in different commissions, and finally in a State/Church commission that took up the question of separation between state and church. The Army had followed these commissions and especially Commissioner Solhaug had already as a CS felt the need to form an Army commission, and made this real when he became TC in March 1975. It became urgent as the State Commission recommended a separation between church and state. Solhaug felt that if this became the outcome Salvationists could no longer keep double membership, but that the Army had to register as a faith community. The commission he started had to look into this as a very concrete question, but not this alone, it also had to look into the Army’s identity and relationship to the present time. This became a broad exercise as he included soldiers and officers alike – he chose the same number of soldiers and officers and had a local officer as the chairman. The representation came from all over the country. The final report was printed and distributed to all corps and departments, so everybody could see the outcome of the work. By this procedure he gave an input to one of the main issues on the agenda of society, the quest for democracy which seemed to be central for different segments of the population. Salvationists wanted the possibility of having a say in decisions and planning, and having a say in how the Army’s identity should be understood. The work took three years and a lot of issues were covered, also the decreasing number of officers and cadets, the finances of officers in light of the increase in income in society at large. The need for education among Salvationists resulting in an educational center in connection with the Army’s Folk High School. For the young people confirmation was introduced and so was modern music style to keep the young people within the Army and avoid letting them feel estranged from Army worship.

In Finland Tor Wahlström addressed some of these issues in his dissertation. The nature of his work was extremely important, but such a work does not become as widespread as a report of a commission.

Two questionnaires with 30 years between

Wahlström’s research covered several interesting features as for instance the percentage of women and men:

Senior soldiers: 17% men and 83% women

Junior soldiers; 21% boys and 79% girls

Active officers: 16% men and 84% women

Retired officers: 9% men and 91% women

I mention these figures, because research shows that women tend to hold on to traditions on a greater scale than men. This in my view might have had an impact on the strong bonds to the Lutheran Church and the wish to continue the traditions and ceremonies from the Church also as Salvationists.

An illustration of such a situation could be seen in Norway when the Army finally registered a faith community in 2005. Some of the couples I spoke with told, that the man had resigned his membership of the church and joined the faith community, while the woman kept her membership of the church.

Another issue Wahlström tried to uncover was if salvationists shared the Army’s official view on the sacraments. The two questions were:

“Do you regard the sacraments

a) necessary for salvation, b) enough for salvation?”

88% answered no to first option, and 8% yes and 4% did not answer. A number did not give an answer to the second option, but of those who answered 92% said no and 8% yes. His conclusion was that Salvationists had a Salvation Army attitude to the sacraments, but in practice they acted as Lutherans.

Concerning the tradition of infant baptism and the Army’s dedication ceremony he asked if the parents should:

a) only bring the child to be dedicated in the Army or

b) bring it both for baptism and dedication or

c) just bring it for baptism in the church:

22% voted for dedication alone, 67% for both baptism and dedication and10% for baptism alone.

Concerning the Lord’s Supper he felt that the result proved his expression Lutheran Salvationists. A number of corps would go to the Lutheran church on Maundy Thursday for communion, in other placed officers and soldiers would attend the communion service privately. His conclusion of this research was that 90% of salvationists had participated in communion within a three-year period.

At the time of Wahlström’s research there was work being done concerning a separation between the state and the church. He asked if salvationists found it

a) desirable,

b) regrettable or

c) don’t know.

41% of the officers and 27 % of the soldiers considered this desirable, while 58% of the officers and 64 % of the soldiers found this regrettable.

The next question concerned the situation if church and state separated. Should the Army register as a free church or continue with the present arrangement? 36% of the officers wanted registration as a free church and 64 % would continue as presently. Of the soldiers 25% wanted a registration and 74% to continue as presently.

Also the question of confirmation came up as Wahlström explained that that the Army in Sweden and Denmark had a confirmation ceremony preceded by teaching and confirmation camps, which the Army’s young people chose instead of confirmation in the church. He underlined that it was without communion. He asked if this would be fitting in Finland. Here he divided the officers into retired and active and then the group of soldiers. Of the active officers 51% were for confirmation in the Army and 46% against, of the retired 22% were for and 75% against, while 50% of the soldiers were for and 47% against.

The next question concerned funerals, where the committal service in Denmark was done by the officer while in Norway by a Lutheran minister. He asked what was most appropriate officer or minister? 53% of the active officers voted for an officer and 45% for a minister. 14% of the retired officers wanted an officer while 83% for a minister. 56% of the soldiers preferred an officer, while 29 % preferred a minister. Here ‘the don’t know’ group was bigger that in the other two.

The last question concerned weddings, if the Army in Finland should pursue legal rights to perform weddings. 56% of the active officers answered yes and 39% no, 22% of the retired said yes and 75% no, while 70 % of the soldiers said yes and 25% no. The majority of both active officers and soldiers were in favor of an officer gaining a priestly function, the soldiers even more than the officers.

Wahlström had a lot of other research questions, but these are the ones for this theme. The majority of Salvationists showed a clear Salvationists faith and attitude. The sacraments were interpreted in Salvationist terms. The doctrine books had been translated into Finnish and Swedish faithfully to the original English version throughout the years, as was the case in Denmark. The use of the sacraments did not rest on ignorance of the Army’s position, but on a deliberate choice. In Finland the first translation into Finnish came in 1929 of the 1923 edition. The beginning of the Army’s work was dominated by Swedish, so most probably the Swedish books were used. In Sweden the first doctrine book was published in 1904 and the translation of the 1923 edition came in 1926. In Denmark the first translation came in 1899, one in 1914 and the 1923 edition came in 1924. The situation in Norway had been that the appendix in the doctrine books concerning the Army’s non-observance of the sacraments had been deleted from the Norwegian doctrine book, that came in 1930. Prior to that the first doctrine book was published in 1901 and was a translation from the very first book from 1881, when the Army still administered the sacraments and with questions concerning the meaning of the sacraments included in the book. None of the other Scandinavian countries did anything like this. It was not until 1975 that the appendix was included in a Norwegian translation. Norwegian Salvationists’ use of the sacraments in the church could rest on ignorance of the Army’s position while in Finland the choice was made on the background of knowledge of the Army’s position. Even so the bonds to the church were stronger in Finland than in Norway.

The percentage of Finnish Salvationists who participated in communion was even higher than the average of members in the church as such.

There can be different explanations for the strong bonds to the church. I have mentioned this with the high percentage of women, another is the high number of newcomers into the Army.

In 2004 I conducted a research in Finland sending out a questionnaire to officers concerning their membership of the church as well as their personal background, such as being first generation salvationists. 76% of the officers were first generation salvationists and were the only ones in their family. A good number of these had parents who had attended the church regularly, so they were no strangers to the church. With such a large percentage of first generation Salvationists and with no demand from the Army to server the bonds to the church, the affiliation to the church could very well linger on, not only as a nominal membership, but also as a more active one, as for instance regular participation in the Lord’s Supper. The vast number of women would support a more active participation in the church, as women often are the ones maintaining the cultural and religious traditions that have been in the family. The questionnaire from 2004 shows that only 5 out of 54 had severed the bonds to the church. 20 considered their membership for an active one, while 31 considered it for passive. Even the passive members and the none members participated in the Lord’s supper – 19 very often, 22 of them 3 – 4 times a year, 13 seldom (once a year or less). 5 underlined how important communion was.

Another factor for Finland has been the political situation. The Lutheran Church was the Church of Finland, even under the Russian empire with the Orthodox Tsar as the head of the church. After independence and during Soviet times Finland lived under thread from the Soviet Union up through the 20th Century. During Wahlström’s research (Wahlström was the TC at the time) the threat from the Soviet Union was very real at least the fear was. The Army considered moving THQ to Turku from Helsinki in case of an invasion from Russia. The enormous underground nuclear shelters in Helsinki were built during this time testify to the fear or threat. Today they are used for underground parking. Under such a political situation with threats from the outside, it has been important to gather round the essential symbols of unity for the people. The Lutheran Church has fulfilled such a role.

The question could be, if this was the role of civil religion.

Civil Religion

The term civil religion is a term that describes a sort of religion that unites a people. For instance in USA you talk about a civil religion alongside other religions, people can be Christians, Jewish or whatever, but there is something American that unites them which evokes religious feelings and belonging:

“The public religious dimension is expressed in a set of beliefs, symbols, and rituals that I am calling American civil religion. The inauguration of the president is an important ceremonial event in this religion.”[1]

Susan Sundback, a Finnish researcher has looked into the question of Civil Religion in the Nordic countries. For Finland she found that a civil religion would build on the religious foundation of the church, and therefore argued that there was a symbiosis between the folk church and civil religion. That was in 1984, but later in year 2000 she looked at the paradox of the fairly strong adherence to the state churches/folk churches in view of the rather weak religious engagement and found that the folk churches had a civil religious function for the Nordic people and that they were centers in a civil religious culture. She did not find civil religion outside the national churches. She suggested that the clearest expression of civil religion was found in the political parties’ programs marked by loyalty towards the church and in the speeches held by church officials on all occasions that underlined the churches’ general social significance. The cooperation between the church and the public sector concerning conscripts, prisoner, patients, and socially exposed people could be seen as examples of civil religious functions. The overall view of the Nordic churches was that they expressed pragmatism toward different issues in society showing a great deal of adaptation to the new developments as well as being theologically liberal. By this they kept the support in membership by the majority of the population. By including the adaptation of the church to society she gave reason for civil religion still to be an issue within the Nordic countries.

This with civil religion suggests membership of the Lutheran church as connected to being a Finnish citizen, to being a member of this society.

I made an little survey among the Finnish officers in 2017 at an officer retreat, which my husband and I were leading, in order to find the percentage of double membership. It seems that 50% were still members of the Lutheran Church, but the other 50% were only members of the Army. This was quite a drastic change. In 2004 there were around 90% who had double membership.

The question of double membership is not as usual in the rest of the world as here in Scandinavia, because of the strong Lutheran churches. General John Larsson compares the double membership with having dual passports. He does that in the foreword to my book p. ix:

“So with inspired application of the principle of adaptation, the pioneers decreed that Norwegian Salvationists could be members of both the Lutheran Church and The Salvation Army. Like people with dual nationality, they could have two passports

The Lutheran passport was not only for decoration. Most Salvationists had their children baptized in the church and many took communion.”

A similar situation worked in Finland.

Which sort of ecclesiology

I want to look into the question of what makes a church a church, what is needed… and most importantly what is needed to be a Salvation Army church among the Finnish officers who were strongly influenced by the Lutheran Church. Had this influenced their idea of what a church is or what is needed to be a church today.

In 1973 according to Wahlström’s research it was obvious that Finnish Salvationists did not consider the Army a church. It is seen as an organization with emphasis on Christianity/Evangelization and Social work.

This identity discussion was not exceptional for Finland as the international Army at the same time started discussing whether the Army was a church or not. During the following 30 years the church identity grew, so in 2008 a little pamphlet, The Salvation Army in the Body of Christ from the General was published. In statement 8 it says: “We believe that The Salvation Army is an international Christian church in permanent mission to the unconverted, and is an integral part of the Body of Christ like other Christian churches, and that the Army’s local corps are local congregations like the local congregations of other Christian churches.”

This came after the Doctrine Book Salvation Story from 1998 for the first time in a doctrine book had a chapter concerning the church – seeing the Army as a church. The chapter was called “People of God”. It was headed by the well-known quotation from Bramwell Booth:

“Of this Great Church of the living God, we claim and have ever claimed, that we of The Salvation Army are an integral part and element – a living fruit-bearing branch in the True Vine.”

This quotation focused on the Army’s belonging to the Church Universal, rather than expressing its belief in the church. Salvation Story underlined not only belonging to the universal church, but expressed a belief in the concrete and visible nature of the church:

“We mean that the Church is Christ’s visible presence in the world, given life by the indwelling of the Holy spirit and called to grow in conformity to Christ.”

Apart from stressing the visible character of the church it also took up membership of the church:

“Membership in the body of Christ is not optional for believers; it is a reality given to all who know Christ, the head of the Church.”

Throughout this short chapter the identity of the church as Salvationists sees it and experience it comes through. The chapter closes with a sort of doctrine (all the summaries were originally new written doctrines, the council was asked to make. The actual doctrines were not revised after all and this exercise in rephrasing doctrines was used as summaries instead)

“We believe in the Church, the body of Christ, justified and sanctified by grace, called to continue the mission and ministry of Christ.”

This sentence show how Salvationists see the Army as a church, the nature and mission of it.

What I found in my research in Norway was a reluctance to identify with the word church as in ordinary language there was only one church – the Lutheran. That was underlined in legislation as well. All other churches were named faith communities, which is a very good description – a community based on faith. In the process of registering the Army as a faith community the discussion came up, if it was possible to be a registered faith community without observing the sacraments, as some Salvationists had the view that the sacraments belonged to the essence of being a church. As far as just before the registration in 2005 a corps officer bought a chalice, because in her view there would be no doubt that the Army as a registered faith community would celebrate the sacraments. The description of a true church within a Lutheran setting is a place where the gospel is preached purely and the sacraments administered truly. This influence from the Lutheran church was seen among some Salvationists. There might be similarities to this in Finland in view of the close bonds to the Lutheran church.

Scrutinizing the international Army’s important documents and books published during the period from 1986 to 2000 concerning ecclesiology I found three important marks of being a church in a Salvation Army understanding. They all related to the overall focus on Mission, to bring the message of salvation to people. They were martyria – the testimony expressed or faith exclaimed, koinonia– the fellowship, that develops people and teaches them to be disciples of Christ, to live as disciples and be his witnesses in everyday life. Fellowships that gather for worship. Diaconia –Fellowships that is directed towards exposed and lonely people and which try to break their isolation. Fellowships, that are alert to social challenges. In short the three were a) bringing out the gospel, b) creating fellowship and c) engaging in diaconia/social work and action.

From my experience working in Denmark, England, Russia/SNG, Finland/Estonia and Norway/Iceland and the Faroe Islands these important marks have been visible in all these countries. They can be seen in corps and very often in social institutions. The percentage is not always 33% for each issue, but they are there at least as a challenge to be taken up seriously. Some corps have a stronger sense of the fellowship element than being in mission, or in other places the social outreach overshadows the worship life of the corps and teaching concerning discipleship, or the internal fellowship of the corps has become the whole horizon, so a blindness towards the social challenges of society has developed. Very few corps have only had the one focus of mission, to evangelize the district. But independent on the obvious realities a sense of all three are present at least as a challenge for the corps to be serious about these three in the life and service of the corps.

Coming back to Wahlström’s research these three elements would most probably be present in the images of Christian/Social organization and Evangelization and Social help organization, which together got 86.1% of those answering. In both there would be the testimony expressed or faith exclaimed as well as engaging in diaconia/social work and action. The aspect that isn’t visible in this way of expressing identity is the fellowship aspect, the koinonia, the fellowship, that develops people and teaches them to be disciples of Christ, to live as disciples and be his witnesses in everyday life. Fellowships that gather for worship. It could be called the more visible church identity. Knowing the Army in Finland this identity has been there, for Salvationists have always gathered for worship, being trained and taught to be disciples of Christ and to be witnesses in everyday life. But there was a reluctance to identify this as a church.

Conclusion

The quote from Catherine Booth which started this article concerning the principle of adaptation together with the Salvation Army’s overall focus on mission has been the leading principles for the Army in Finland as well as for the Army in the other Lutheran countries of Scandinavia up through its history. The question: “Shall we reach the whole population or become a protestant sect?” was originally answered in favor of reaching the whole population or an attempt to do so. It succeeded in doing this so the Army was known and welcomed all over the country also into people’s homes. The question today might be answered differently in a very different time, but our history can serve as an inspiration for us today to be interpreted in a relevant way. Both the principle of adaptation as well as the question or mission strategy are still there as a challenge for us to answer.

[1] Bellah, ”Civil religion in America”, 40-55

Kære Gudrun

Det ser spændende ud, det vil jeg i nærmeste fremtid nærlæse. tak herfor.

Blessings

Vibeke

LikeLike

This is most interesting, living as I do in a Lutheran environment and seeing a very weak church which has suffered a massive loss of members. The Army, also, has had to close many corps. One aspect of General Larsson’s account worries me: that the Army was prepared to remove a doctrine to accommodate Lutheran sensitivities. Also, not mentioned in this story, is the difference between the Lutherans and the Army about the Sacraments and being born again, the latter surely affecting the Army’s evangelistic zeal.

On Wed, 12 Feb 2020, 10:39 Salvationist viewpoints, wrote:

> lydholmwritings posted: ” The Army within the Russian empire General John > Larsson quotes Catherine Booth from 1880 in his foreword to my book: > Lutheran Salvationists?: “The Army’s achievements are built on the great > fundamental principle of adaption.” This can be see” >

LikeLike