Symposium on Ecclesiology and Ethnography

St. John’s College, Durham

10-12 September 2013

The practice of making Doctrine: From propositional to narrative Doctrine in a global denomination

by Gudrun Lydholm

1. Introduction – Salvation Army practice of making doctrine

A global denomination such as The Salvation Army is faced with the challenge of communicating its doctrines and ethos in such a way that it makes sense to ordinary Salvationists with diverse cultural and religious backgrounds around the world. Documents have to be translated into many different languages and still be true to the original texts. This challenge might not have been at the forefront of the agenda when doctrine books were prepared and written in the past. The lack of focus on the issue of translation has made room for misinterpretations on vital issues[1].

The Salvation Army originated in England as an evangelical working class religion and spread from there to the rest of the world. The origin of Salvation Army Doctrine books dates back to 1881 just on the brink of the Army’s expansion out of Great Britain[2]. The first doctrine book[3] was a little catechism[4] primarily for the benefit of the cadets training to become officers and was built on previous material for the cadets’ classroom. It was also published as an answer to accusations in the press that The Salvation Army had material that was secretly taught to the cadets. Different editions and revisions of this first doctrine book were published in 1892, 1900, 1904, 1906, 1907, 1911, 1913 and 1917. These editions were called ‘the little red ones’ and were like small pocket books.

In 1923 a new type of doctrine book[5] appeared. It was a more solid account of doctrine than the small catechisms had been. It had eleven chapters with different sections mainly following the eleven Articles of Faith[6]. This Handbook of Doctrine was published in new editions several times until 1969 when another doctrine book[7] was prepared. The 1969 book reflected a broader understanding of Christian doctrine. It began for example with a chapter explaining the importance of studying doctrine as well as the limitations of such a study. Appendices on the Apostles’ Creed and the Nicene Creed signaled the Army’s place within the Church universal. Still it was a propositional account of doctrine like the 1923 book and the arrangement of eleven chapters reflecting the eleven doctrines was similar as well. All the doctrine books so far had been written by British officers and prepared by mainly British Doctrine Councils[8]. The internationalism of the Army was taken for granted even though it was not in focus when preparing the doctrine books.

A real change came in 1998 with the publication of Salvation Story[9] followed in 1999 by Salvation Story Study Guide[10]. The propositional nature of the doctrine books was exchanged for a narrative approach in communicating doctrine.

1.1.The reason behind this change

This new style of a doctrine book was written by an international doctrine council as a joint venture. In 1992 the International Doctrine Council[11] was appointed by The Salvation Army’s world leader General Eva Burrows[12] to write a new doctrine book. The council was encouraged to make a fresh approach to SA doctrines, to think and discuss freely without restrictions and not to be bound by previous doctrine books. The mandate given was to debate, evaluate and rewrite a doctrine book, a solid theological book written in a way that communicated to ordinary Salvationists.

There were different reasons for making the change from a British Doctrine Council to an international one. A letter from Eva Burrows who is Australian explained her reasons for the change. The decision was made in 1992 and the letter was from 2013 so ‘present day’ agenda and the distance of well over twenty years have to be taken into account, but this is how she considers her decision today:

“Being an internationalist, and having served in so many parts of the world including Africa and Asia, I was surprised that the Doctrine Council was entirely British….I felt I needed a world view in discussion on our Articles of Faith…….I wished the book to be more user friendly for ordinary Salvationists who could read it and enjoy it, in more contemporary, fresh language. I also have seen the struggles of translators in Sri Lanka and Zimbabwe to get to grips with the last Doctrine Book, where there was so much repetition in the language, that they seemed to translating the same thing over and over again.”[13]

Eva Burrows also mentioned that the Promises section of the Articles of War/Soldiers Covenant[14] was revised and modernised in 1988. She felt that it was timely for the Doctrine Council to look at the 11 Articles of Faith. I will return to that process and the outcome of it.

In my letter in May 2013 to Eva Burrows I had suggested that the process round the BEM document[15] prepared the way for having a different approach to the writing of a doctrine book. Her answer was that it was not the BEM document that inspired her to form the International Doctrine Council, but the other reasons already mentioned. However when I look into this whole process of responding to the document it at least gave the members of the Doctrine Council inspiration to work as a committee also in their task of writing the new doctrine book.

The BEM document was considered to be a discussion paper for the member churches of WCC to respond to. The Salvation Army took up the challenge and formed a study group at International Headquarters in London. The group made a draft that was sent to Army territories around the world asking for responses to the draft document. The official response from the Army was given in 1985[16]. Into that response were included responses from twenty territories as well as from individuals apart from the study group. Also the International Leaders conference in Berlin in 1984[17] had the Lima document on the agenda. To place this issue here signaled the utmost importance of the matter to all Army leaders, meaning that the issue could not be ignored at national level. The BEM document also came up as a question at the High Council[18] of 1986. Eva Burrows was one of the nominees and the one to be elected. One of the questions to the nominees was: “What is your view of The Salvation Army’s recent response to the Baptist/Eucharist/Ministry Lima Document?”[19] The response from Eva Burrows was two paragraphs ending with this statement: “The other helpful effect of our response to the BEM document is that it proved enriching and challenging to us, as we prepare more adequately to train our own people in the understanding of our position.”[20]

Even though the BEM document was not at the forefront of Eva Burrow’s decision to form an International Doctrine Council, the issue of publishing a new doctrine book that in a more contemporary form aimed at the ordinary Salvationists all over the world certainly fulfilled her response “as we prepare adequately to train our own people in the understanding of our position”. The BEM document was not explicitly the reason for this new doctrine council, but implicitly it was there at least as an inspiration that gave an atmosphere of thinking and discussing theology to a greater and much broader extent that had previously been the case.

1.2 A new approach in writing doctrine

The International Doctrine Council met in London for the first meeting in July 1992. Little by little the meetings extended from two short days[21] into three to four long days of conference in residence[22] from twice to four/five times a year changing the venue from an office at International Headquarters to the Training College for cadets. This meant that the debate continued during meals and breaks. All were aware that the continuing debates within the group had to result in a written text which all could agree on. Each member prepared written texts on different themes as the basis of the debates.

After four to five years when the first draft was ready it was sent out to all Salvation Army territories in the world[23]. Many territories made working groups to read and comment the draft. In the territories that did not sent the draft to be examined and commented by working groups the Territorial Commander responded after having consulted a few other persons. The responses coming in were absolutely overwhelming. Many of the working groups had prepared thick documents filled with suggestions for a different approach, another style, different language and complain about the theology coming through the first draft. Others agreed with both style and theology. A retired officer (Lt. Colonel Robert Waddams) was asked to read through the enormous amount of paper and to sort according to themes and then to write an agenda of problem areas, questions and suggestions for change that had been received. Even with all this done the amount the council had to consider was considerable. The revision based on all the input from the Army world took between one and two years. The many voices from around the world were listened to and reacted upon in one way or another. Because of this lengthy process of revision a world view came into the discussion not only through the members of the council, but through all the comments on the first draft.

The narrative style was kept and so was the arrangement of the chapters based on themes and not on individual doctrines. The Doctrine Book was authorized by the General and finally published in 1998. In the introduction to Salvation Story the narrative form is explained:

“It is narrative in form, so that teaching is presented in short paragraphs, rather than point by point. This should enable the progression of thought to be clearly seen and allow for flexible use in both study groups and the classroom. The narrative style means that we examine the truths of our faith on two levels, both as the work of God in history which accomplished our salvation, and as the record of our own journey of faith, from sin through to salvation and holiness. The narrative approach is reflected, too in the Handbook’s title: Salvation Story. Salvationists base their understanding of doctrine on the witness of the Bible, the living word of God. Our Articles of faith make that clear, and therefore this book seeks to be faithful to Scripture.”[24]

Salvation Story was formed in a more systematic way[25] than its predecessors and theologically it covered more ground, but even so it was not a full academic systematic theology. There were no chapters on methodological or hermeneutical considerations or sources of theology and the like. Salvation Story was more to be seen as a kind of catechism that could be used for teaching purposes or just read and studied by Salvationists and others who wanted to know what the Army believed. In order to substantiate Salvation Story and put doctrine and theology even more on the agenda of local corps communities both in teaching and worship Salvation Story Study Guide was produced.

“Perhaps the purpose of the Guide can best be summed up by describing it as a link between the doctrinal teaching of the Handbook and the thinking and living of the individual Salvationist as well as the Salvationists community in particular settings. It is not enough to assent to the truths of Scripture and to the Army’s doctrinal positions. Our faith must penetrate, transform, and enliven both the mind and the life of us all. It must be a living faith. It must be our own faith. The purpose of the Guide is to stimulate our ownership of a faith that is alive and thought out.”[26]

As can be seen from the introduction to the Study Guide it was vital for the Army ‘to stimulate an ownership’ of the faith so it could be transformed from an intellectual doctrinal exercise to a living faith. To help this process on its way all the chapters in the Study Guide included the following sections: 1) Belief – this covered a) historical summary b) the importance of the doctrine to the Christian faith c) issues for Salvationists d) the essentials of the doctrine e) discussions and questions f) further discussion (here the text was digging deeper into the theology behind the doctrine). 2) Life – case stories and questions for group discussions. 3) Worship – ideas for personal and corporate worship. 4) Bible studies.

It was at the top of the agenda of the Doctrine Council that both books should be readable to ordinary Salvationists at the same time as more scholarly minded Salvationists should be able to recognize a more profound theological base of both Salvation Story and Salvation Story Study Guide. When the books were published reviews were divided between ordinary Salvationists and theologians who felt this aim had been reached to others who felt it missed the goal. The more conservative Salvationists missed the former practice of proof texting every paragraph and the fact that the chapters were built on themes and not on following the eleven doctrines. There were still Bible references, but that was as a selection of relevant references at the end of the sections.

1.3 Rewriting the eleven doctrines

Apart from writing a new doctrine book the Doctrine Council had been asked to rewrite the 11 doctrines of The Salvation Army. A lot of work and discussions went into that exercise and all members including the corresponding members individually wrote different affirmations of faith. In the Study Guide these are printed[27] including one in German and French. The number of doctrines span in these different affirmations of faith from 9 to 3. Following this exercise, the work finally centered round rewriting 11 doctrines, making room for a doctrine on the Church within the eleven. The chapters of the book had mainly followed these new doctrines. Therefore when it was decided by the General[28] that the doctrines should not be changed the council kept them and decided that they might be used as summaries of each chapter. The General[29] who authorized Salvation Story agreed that the new doctrines could be used in such a way.

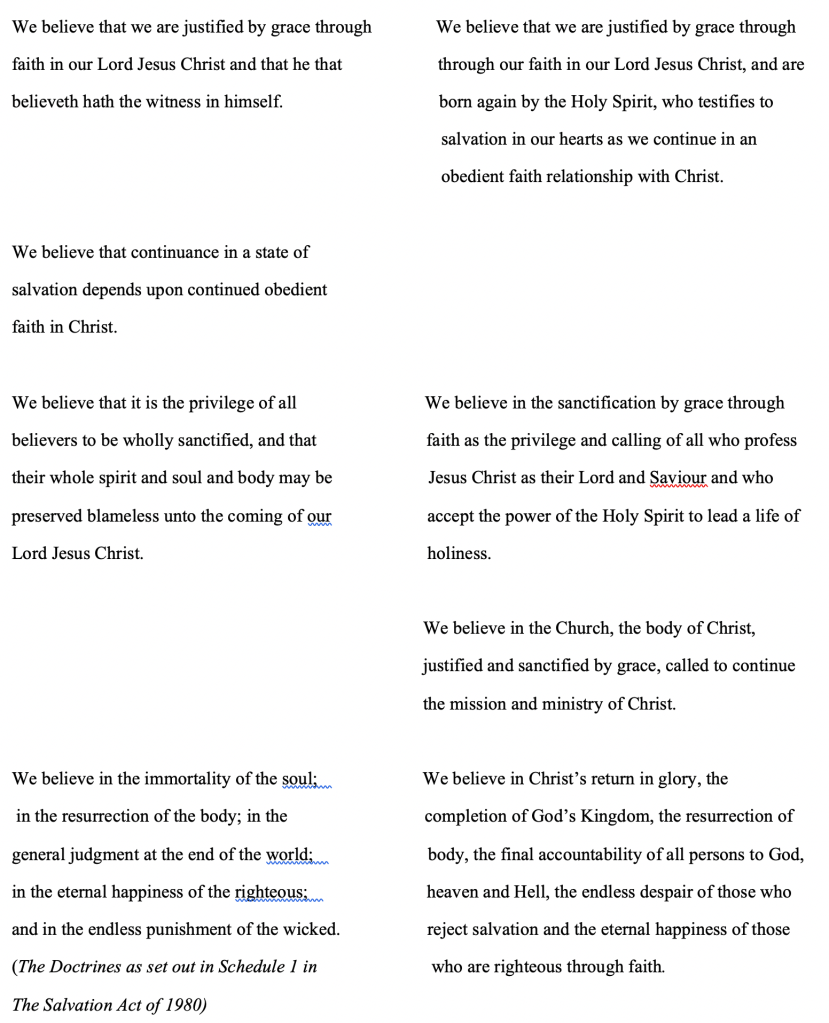

I will visualize the difference between the eleven doctrines and the contemporary summaries from Salvation Story[30] by writing them side by side. This illustrates the contemporary theological agenda of Salvationist theology especially the last twenty years of the 20th Century.

As mentioned the rewritten doctrines stood as summaries in Salvation Story. They took up Christian beliefs that have always been implicit into Salvation Army faith, but not been explicitly expressed as for instance the resurrection. Also a greater focus on the Trinity can be seen. An outcome from this focus was that the person of the Holy Spirit became more prominently explored in the doctrines.

During the years of writing Salvation Story the Doctrine Council received questions on faith from different parts of the world which the council had to deal with. They were received by the General who then passed them on to the council. For example a group of Australian youngsters wrote a letter expressing their dismay with the fact that the resurrection of Christ was not stated in the 11 doctrines. Another question coming in was why there was no doctrine explicitly on the person of the Holy Spirit. Questions like these are reflected in the summaries.

1.3 Conclusion

The summaries did not survive into the next doctrine book from 2010. The General of the time[31] was very critical to the changes made in Salvation Story and so were others who felt it departed too much from the previous books. The General decided to publish a doctrine book more in line with the Army’s tradition for doctrine books. This book The Salvation Army Handbook of Doctrine[32] amalgamated and revised Salvation Story and Salvation Story Study Guide and altered the chapters to follow the 11 doctrines. Bible references were again used as proof texting after each paragraph. This Doctrine Book retained a chapter on ecclesiology which in Salvation Story had build on a new doctrine on the Church[33]. Here it was not a part of the doctrines and the chapters concerning the doctrines, but a separate chapter which included much of the material from the other two books. In 2008 The Salvation Army issued an ecclesiological statement The Salvation Army in the Body of Christ. It was printed as an appendix to the doctrine book.[34] Both the 1998 and the 2010 doctrine books are used around the world. Not all territories have started the process of yet another translation. Some territories had only translated Salvation Story and never translated Salvation Story Study Guide. Included in the 2010 doctrine book a lot of the material from the study guide appeared.

As can be seen the work with doctrine books in The Salvation Army is a never ending story – revisions and new books will most probably be the case in the future as well as in the past.

[1] An example of this would be the translation of the doctrine of holiness into the Scandinavian languages. The texts would easily give the impression that the Army believed in holiness as sinless perfection.

[2] It expanded to USA in 1880, to France and Australia in1881, to India, Canada, Switzerland and Sweden in 1882 and so fort.

[3] The Doctrines and Disciplines of The Salvation Army. Prepared for the Training Homes by order of the General, 1881 London

[4] It resembled the catechism of William Cooke from the Methodist New Connection, A catechism embracing the most important doctrines of Christianity, 1851 London

[5] Handbook of Salvation Army Doctrine, 1923 International Headquarters, London

[6] See The Salvation Army Articles of Faith on p. 6-8

[7] The Salvation Army Handbook of Doctrine, 1969 International Headquarters, London

[8] The Doctrine Council being involved in dialogue for preparing the 1969 book had a Canadian member, Commissioner Clarence Wiseman, but the one writing it was British, Lt. Colonel Gordon Mitchell.

[9] Salvation Story, Salvationist Handbook of Doctrine, 1998 The Salvation Army International Headquarters, London

[10] Salvation Story Study Guide, Salvationist Handbook of Doctrine, 1999 The Salvation Army International Headquarters, London

[11] The members were David Guy from UK, Earl Robinson from Canada, John Amoah from Ghana, Phil Needham from USA, Ray Caddy from UK, Christine Parkin from UK and Gudrun Lydholm from Denmark. Apart from the actual council there were corresponding members from Australia, Korea and Switzerland.

[12] Eva Burrows was General from 1986 – 1993

[13] Letter from Eva Burrows 29 May 2013

[14] The Soldiers Covenant is signed by all soldiers at the ceremony when they are ‘enrolled’ as soldiers. It contains the 11 Doctrines of The Salvation Army and a section on promises for a life style of moderation and engagement in the mission of the Army.

[15]Baptism , Eucharist and Ministry 1982, Faith And Order paper no. 111, World Council of Churches, Geneva . It is perhaps better known as the Lima Document

[16] Baptism, Eucharist and Ministry, World Council of Churches, Commission on Faith and Order Paper no. 111, a response from The Salvation Army, International Headquarters, London 1985. Five years later the Army published One Faith, One Church, The Salvation Army’s response to Baptism, Eucharist and Ministry, The General of The Salvation Army, London 1990. The book gave information of the process apart from the actual response.

[17] Such a conference is chaired by the General. Here in Berlin the General was the Finnish Jarl Wahlström who also was the one that had decided that the Army should engage itself on this level in the BEM process. Territorial Leaders from around the world and from International Headquarters would be present. Each general has at least one International Leaders Conference in his/her term of office.

[18] The High Council elects the General. Membership of the High Council includes all Commissioners and all other Territorial Leaders. In the eighties it was all Commissioners and Territorial Commanders with the rank of Colonel if they had been in this position for two years.

[19] Minutes of The High Council 1986 p. 136 Private Archives, Copenhagen

[20] Ibid p. 139

[21] From 9am to 4pm

[22] From 9am to 10pm

[23] At that time in 1997 the Army worked in 103 countries

[24] Introduction to Salvation Story p. xiv

[25] The title of the chapters illustrates this: 1) Word of the living God, 2) The God who is never alone, 3)Creator of Heaven and earth, 4) God’s eternal Son, 5) The Holy Spirit, Lord and giver of life, 6) Distorted image, 7) Salvation Story, 8) Salvation experience, 9) Full salvation, 10) People of God, 11) Kingdom of the risen Lord

[26] Introduction to Salvation Story Study Guide p. vi

[27] Salvation Story Study Guide p. 123 – 131

[28] The General was the Canadian Brammwell Tillsley ( 1993-1994). His decision was influenced by the Advisory Council to the General. It was a different Advisory council that the one Eva Burrows had consulted.

[29] The General was the American Paul A. Rader (1994-1999)

[30] This is based on a paper I presented at bilateral talks between The Salvation Army and the World Methodist Council at Sunbury Court, London 2 June 2003 where I commented on the difference between the two sets of doctrines. The full paper Salvation Army Doctrines was printed in Word and Deed, A Journal of Salvation Army Theology and Ministry, November 2005 p. 33 -54

[31]The General was the British Shaw Clifton (2006 -2011). It was an unusual step to revise a doctrine book so soon after the publication of Salvation Story. The task was given to a British officer and not the Doctrine Council. Normally the changes had happened because of things being outdated as for instance for language reasons, not because of a disagreement with a publication a previous General had authorized. The Advisory Council to the General had been changed into The General’s Consultative Council by the British General John Gowans (1999 – 2002). In this council the General would be present in consultation with leaders from around the world. The rationale was to include even more ‘voices’ from different parts of the world. All leaders eligible for the High Council would be members. The presence at the council would rotate so all would attend at least once in a time span of 2 -3 years. General Shaw Clifton kept this council, but altered the agenda to be debates on general themes and not consultation on specific matters. He only used the executive council at IHQ for this. The outcome was that the ‘voices from around the world’ were not heard in different matters such as a revision of the doctrine book. In a hierarchy such as the Army’s, administration like this was possible, but had been more consultative in previous years.

[32] The Salvation Army Handbook of Doctrine, 2010 Salvation Books, London

[33] It was the first time in SA history that a doctrine and a chapter on ecclesiology were expressed in a doctrine book.

[34] Appendix 5 p. 310 – 318