I will introduce the theme with a poster that illustrates a Christian response to the social question, but which also looks ahead to the social gospel. In my interpretation it implies the reason why the social question came urgently on the agenda in Norway and all over Europe.

It is a rather forceful illustration, a young female Salvationist is positioned as a sort of statue of liberty, pointing to something greater, something liberating, perhaps to the message of the kingdom of God. This catches the attention of the crowd. We can only see some faces looking upwards and some of the hands lifted up in prayer or petition. It is in the glimpses of the crowd I implicitly can see some of the worry behind the social question that was present in society. As long as the hands were lifted in prayer or petition, there was no danger, but these hands could as quickly turn into fists ready for fight or for revolution. The silk lining of the Salvationist’s cape is red, which is the main colour in The Salvation Army flag symbolizing the saving blood of Christ. If these hands of prayer and petition turned into fists the red colour would symbolize revolution with human bloodshed as a result. The child covered by the other side of the cape looks rather skinny and may be a symbol of poverty that also includes the children. The illustration does not transmit an image of charity facing the poor or the oppressed – in order to create a bond between a charitable giver and a grateful receiver. The picture is pointing beyond such a situation, to a higher goal. The young woman is not at all an illustration of a slum sister – that cape would not fit in with scrubbing floors or caring for the sick and dying and there is no particular care for the child either. It is just placed there as a symbol of poverty. The illustration is from 1919 from a social campaign in USA made by Fredrick Duncan. The original poster had the text: “A man may be down – but he is never out.” However, the illustration has also been used as the front page of the 2010 edition of Walter Rauschenbusch’s A Theology of the Social Gospel that originally was published in 1917.

The social question

I will start with explaining the social question. It came forcefully on the agenda in Norway during the nineteenth century due to the growing industrialization and the social consequences as poor housing in crowded areas of the cities and the uncertainty of the workers’ conditions such as wages, work hours or unemployment. The poverty as a result of this called for action both politically as well as from society at large, not least the church. There were no regulations for child labour or for jobs destroying health and shortening a life span as for instance in the industry of producing matches. There was no disablement insurance. As a response to the situation poverty laws were passed in 1845 and 1863. They were rather restricted. They only covered bare necessities for the deserving poor, who were in the situation of poverty through no fault of their own. This public poor relief did not cover the need. There was a demand for private initiatives. This came mainly from the church and Christian organizations, but not only also doctors, employees from the public sector as well as the workers themselves… and taxpayers took responsibility.

The expression ‘the social question’ was mainly used from 1870s and onwards. It was realized that the problem had both a political as well as a social side. Poverty could be politically dangerous as was clear from the revolution expressed in the Parisien Commune in 1871. The workers in Norway were increasingly being organized from 1870 and onwards. Norwegian society had already seen an example of organized workers associations through the Thrane movement in the years from 1848-1851. Marcus Thrane the founder of the movement wanted justice. His used Biblical vocabulary and claimed that socialism was the true Christianity. He disagreed with the dogmatic faith of the church, but considered liberty, equality and fraternity as central in the message of Jesus together with the dual commandment of love. He founded workers’ unions that included groups that would not naturally be included in workers’ unions as they appeared later. The unions included smallholders, artisans and workmen and spread to great parts of Norway. In 1850 a petition with a number of motivated demands such as suffrage, better schools, cheaper grain, measures against extortionate interest etc. was given to the King signed by nearly 13 000 people. At its peak in 1851 when the leaders were arrested it had around 30 000 members.

The social problem had to find a political solution through social politics. The inspiration came from Germany where the concept was phrased and signaled a new role of the State with a public responsibility for the citizens. There were two models, one was an insurance model financed by premium. The other was a public assistance model as in state pensions or poor relief. In Norway the insurance model won the day around the turn of the century. In 1892 a Protection Act that regulated child labour and working hours came into being and in 1884The Disablement Insurance Act followed and in 1909 the Health Insurance. Universal suffrage for men came in 1889 and for women in 1913.

The church was involved also in the public help as ministers took the chair in the public committees for poor relief and when this system changed they stayed on as members. The majority within the church wanted to manage the poor relief independent of the state or even as an alternative to the state. It did not agree on the basic foundation for the public poor relief. It concerned rights and duties: the poor had the right to receive help and other citizens had the duty to pay tax for the poor. It was considered demoralizing or depraving, because the poor might be passive receivers instead of working to better their situation. The key word was voluntariness. The rich should give not as a duty but on a voluntary base. They would give as an act of charity and the poor should receive this with gratitude. This would bond the rich and poor together, one showing charity the other gratitude.

Ministers from within the church such as Honoratus Halling in Christiania formed alternatives to Thrane’s workers’ associations which should turn the workers’ attention away from revolution to Christian solutions such as an integration of the working class into society as it was. He started for instance Sunday schools for adults and library for the workers. Another example is the theologian Eilert Sund who founded Kristiania’s Workers Association where the workers could take part in social gatherings and listen to educational lectures. Both Halling and Sund founded sick benefit associations. The primary person in founding the Home Mission Movement was Gisle Johnson, lecturer and later professor at the Theological Faculty. He defined the mission of the movement as a free association of Christians who with charitable work would fight society’s sinful depravation and earthly misery (temporal). It started initiatives to alleviate poverty and social need, especially the Home mission Movement in Kristiania which was established in 1855. He supported the model of charity given and gratitude received.

There were, however, other voices from within the Norwegian church that underlined justice and solidarity. This came at the turn of the century and the beginning of the 20 century. Especially ministers in Kristiania such as Michael Hertzberg who for a period took industrial work to experience the workers situation and Christopher Bruun who characterized the church’s diaconical work as ‘crumbs which fell from the rich man’s table’. Much stronger measures had to be used that would change society. Another example was Kristen Skjeseth who became curate resident in Narvik from 1909. In 1910 he published Kirken og arbejderklassen (The church and the working class) that voiced resistance against the dominant thinking within the church by this statement: ‘We do not want charity, but righteousness’. The vicar in Narvik, Johs. J. Andersen, shared a similar attitude. Narvik had in few years developed from a small village with fishers and farmers to a busy center with industry due to the construction of an industrial harbor and a railway to the ore mines in Kiruna in Sweden. There was a demand for ore in the industry around Europe. This meant an influx of fishers, farmers and smallholders who saw better prospects in this new industrial center. The church had no organized social initiatives, but a strong social conscience. The ministers’ attitude was that there should not be competition between the church and the public social work.

“The demand for social justice and the will that nobody shall be in want is so strong among the majority in Narvik that Christian charity will reach furthest by cooperation with the public institutions.” ( p. 142 Aukrust 1990)

It was an ideal to Christianize the public poor relief. Both of these ministers became politically active in local politics as well as on national level.

Such an attitude with focus on righteousness instead of charity was an example of the social gospel that took its inspiration in the concept of justice in the message of the prophets such as Amos, Hosea, first Isaiah and Micah.

The social gospel

Central for the social gospel was redemption for society as well as for individuals. The fight for righteousness and justice belonged to the core of this, with the overall focus on the kingdom of God, not as something heavenly in the far future, but building the kingdom of God here on earth step by step, an expectation of bringing in the kingdom of God. One stream of the social gospel was a progressive social Christianity with an interest in transforming both the individual soul as well as society’s unjust structures.

The Social Gospel Era is generally assumed to be starting around 1880s and being influential till late 1920s. One of its most important exponents was Walter Rauschenbusch, a German –American Baptist who ministered for ten years in New York before becoming a professor of church history at Rochester Seminary in the state of New York. His main concern was to search the Scriptures for a message to the circumstances of industrial society. He claimed that the social gospel was neither new nor alient. It was a proper part of the Christian faith in redemption from sin and evil. It was the oldest gospel of all as it was built on the foundation of the apostles and the prophets. If the prophets talked about redemption they meant the social redemption of the nation. The kingdom of God was central in the proclamation of the gospel which Jesus brought. This emphasized ethical teaching and practice.

I will share a few quotation from Walter Rauschenbus’ book The theology of the social gospel to give an illustration of the images and the language used:

“Now as soon as the social gospel began once more to be preached in our own time, the doctrine of the Kingdom was immediately loved and proclaimed afresh, and the ethical principles of Jesus are once more taught without reservation as the only alternative for the greedy ethics of capitalism and militarism…It is a revival of the earliest doctrine of Christianity, of its radical ethical spirit, and of its revolutionary consciousness…..(p. 26)

The church is primarily a fellowship for worship, the Kingdom is a fellowship of righteousness. When the latter was neglected in theology, the ethical force of Christianity was weakened: when the former was emphasized in theology, the importance of worship was exaggerated. The prophets and Jesus had cried down sacrifies and ceremonial performances, and cried up righteousness, mercy, solidarity” ( p. 134)

“Reversely, the movement for democracy and social justice were left without a religious backing for lack of the Kingdom idea. The kingdom of God as the fellowship of righteousness, would be advanced by the abolition of industrial slavery and the disappearance of the slums of civilization..” (p. 136)

The language used by the spokesmen of the social gospel had some resemblance to the language used by the workers’ unions, words like: capitalism, militarism, industrial slavery – social justice, democracy, righteousness.

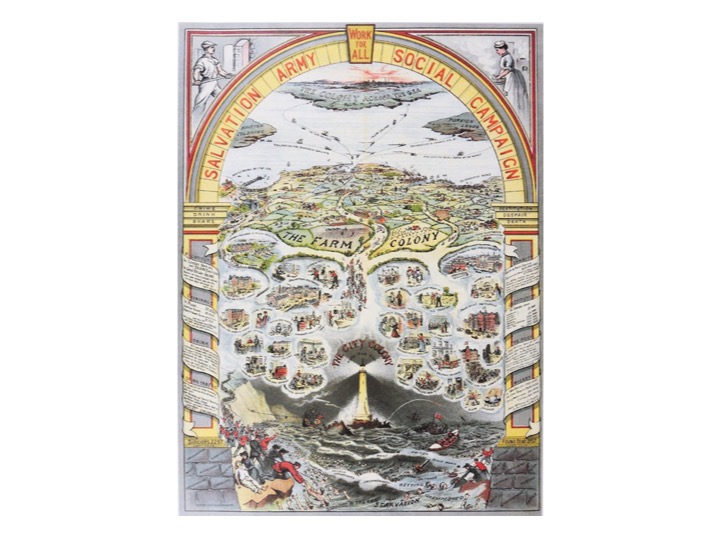

I will use another poster as an illustration of the social gospel, built on the social question. It is the poster that was included in the book: “In Darkest England and the Way out” by William Booth, that was published in 1890. It visualizes the social problem in England with this rough sea. The waves carry names of different social problems such as starvation, unemployment, homelessness, despair, misery, slavery, prison, rags, drunkenness, outrage etc. The foot of the pillars shows a number of suicides and the number of people found dead based on statistics from the previous year. Up the columns there are numbers from statistics of different social evils. The center of the social campaign says: “Work for all”. The sea represents the social question, but on land both the city colony, the farm colony and the colony across the sea represent the social gospel in action. This was charity in action, but it was built on the sense of righteousness, on the message of the old prophets, on demands of justice for all. Central in the book was the cap horse charter:

“Every Cab Horse in London has three things; a shelter for the night, food for its stomach, and work allotted to it by which it can earn its corn. These are the two points of the Cab Horse’s Charter. When he is down he is helped up, and while he lives he has food, shelter and work.” (p.19 and 20).

The scheme shows redemption for society by different initiatives – a city colony, a farm colony and a colony across the sea. Examples of the city colony could be poor man’s Metropole, poor man’s bank, poor man layer, work men restored to masters, salvation factories – here for instance the match box making. In Norway there was a production of matches with the terrible consequences for the workers – the phossy jaw, a painful decease in the jaw leading to early death. The Darkest England scheme started a match factory in London where the toxic yellow phosphor was exchanged for less harmful material, wages were raised and work hours regulated to be from 8am to 6pm with 1 hour for lunch and two tea breaks at 11 am and 4pm. The rule was ‘Fair wages for fair work’. This slogan appeared on the first boxes of matches. Other slogans were: ‘Love thy neighbor as thyself’, ‘Bear one another’s burdens’ and ‘Our work is for God and humanity’. The factory was in operation from May 1891 to November 1901 when it was taken over by the British Match Company.

The Darkest England Scheme illustrates the focus of the social gospel. The vision of changing society so the social evils would be eradicated is present. It is not changing society through politics, but by building up God’s kingdom on earth to prepare for the return of Christ. In my view William Booth was close to postmillennial thoughts and beliefs. Postmillenialism held the view that there would be a period of the Kingdom of God on earth, or a thousand year of ‘power for the gospel’ followed by the return of Christ. Similar thoughts as this belonged to the social gospel.

Colonel Othilie Tonning

One of the persons in Norway for whom the Darkest England scheme became inspirational and instrumental for her own life and work was Colonel Othilie Tonning. In June 1934 three years after her death the English Salvation Army paper, The Deliverer had a series of articles called ‘A Platform for Women’ where Othilie Tonning was portrayed. The article included quotations from her own writing. In one of these she told about the influence of this book:

“His plan for saving the outcast took my youthful mind with such a force and power that I thought it would pave the way to the Millenium! When later I became the Social Secretary, the understanding and impressions I had received from Darkest England helped me always to remember the soul behind filthy rags and dirty habits, the spark of eternal life in every man, and our duty of ‘making the connection’ between it and the eternal Originator”

As a young woman she was very active in the fight for universal suffrage for women and for equality between men and women on all levels of society. 17 May 1890 she participated in the march for voting rights for women and held the public speech with the same theme in her hometown of Stavanger. Frelsesarmeen opened the work in Stavanger in 1890 and very soon Othilie Tonning started attending its meetings. The fact that the two pioneers were women made an impact on her and drew her to the meetings in order to see what this was all about. She joined the Army the same year and her whole life was lived in the service of Frelsesarmeen. She was in charge of Frelsesarmeen’s social work from 1898 to her retirement in 1924, and again from 1929 to her death in 1931. She was the one that made a solid foundation for Frel sesarmeen’s social ministry and really expanded the social work all over Norway at the same time as she placed it on the map of politicians as well as the general public. She used her skills as a public speaker as well as a writer to further issues central to her and Frelsesarmeen. She was also active in local politics in Kristiania and was elected to the Town Council where she served as member from 1908 – 1916. First she was elected for the Temperance society then for Venstre. (I think it would be an equivalent for the Liberal Party today). She was very active in all issues concerning alcohol politics, but this issue stood not alone. All matters concerning women’s rights and social problems had her full attention. She could stand as an example of how the Darkest England Scheme or the social gospel was implemented on Norwegian soil.

The work of Frelsesarmeen, the Home Mission Movement, the different ministers within the church and many other individuals and groups made up a co-operation between the public and private initiatives as an answer to the social problem. This formed what Anne-Lise Seip called ‘socialhjælps staten’ – the social help state, that was the forerunner for the later welfare state.

I consider the Darkest England scheme as an expression of the social gospel. The focus on righteousness and social justice which a number of ministers within the Norwegian church such as Kristen Skjeseth in Narvik underlined are in my view also expressions of the social gospel.

The era of the social gospel ended. Some consider this to be at the end of the 1920s and others at the end of World War II. The social gospel was criticized for having too high a doctrine of humanity and too low a doctrine of sin by Reinhold Niebuhr , who contributed to the 20th century political theology. (He was on the other hand criticized for being too pessimistic about human nature and overstressing the fallenness of humanity). However, in the 1960s the social gospel gave inspiration to the civil rights movement with Martin Luther King in USA and perhaps even more to liberation theologies in South America during the seventies and onwards. The theology changed, but the Kingdom of God and redemption of society were still central. It went further and developed so it stressed an option for the poor.

The last power point will stand as an illustration of the reason for Christian involvement in solving the social problem as well as for the inspiration of the social gospel: Original quotation by Irenæus, Bishop of Lyon (app. 130 – 200) : Gloria Dei, vivens homo ( the glory of God is man who is alive). Here the focus is on the very being of man.

The quotation was adapted by Archbishop Oscar A. Romero, El Salvador (assassinated in 1980): Gloria Dei, vivens pauper (the glory of God is the poor who is alive).

Feeding pogramme Moscow station Russia 1998

Litterature: Please contact by email gl@fhmail.dk for a list of supporting litteratur.